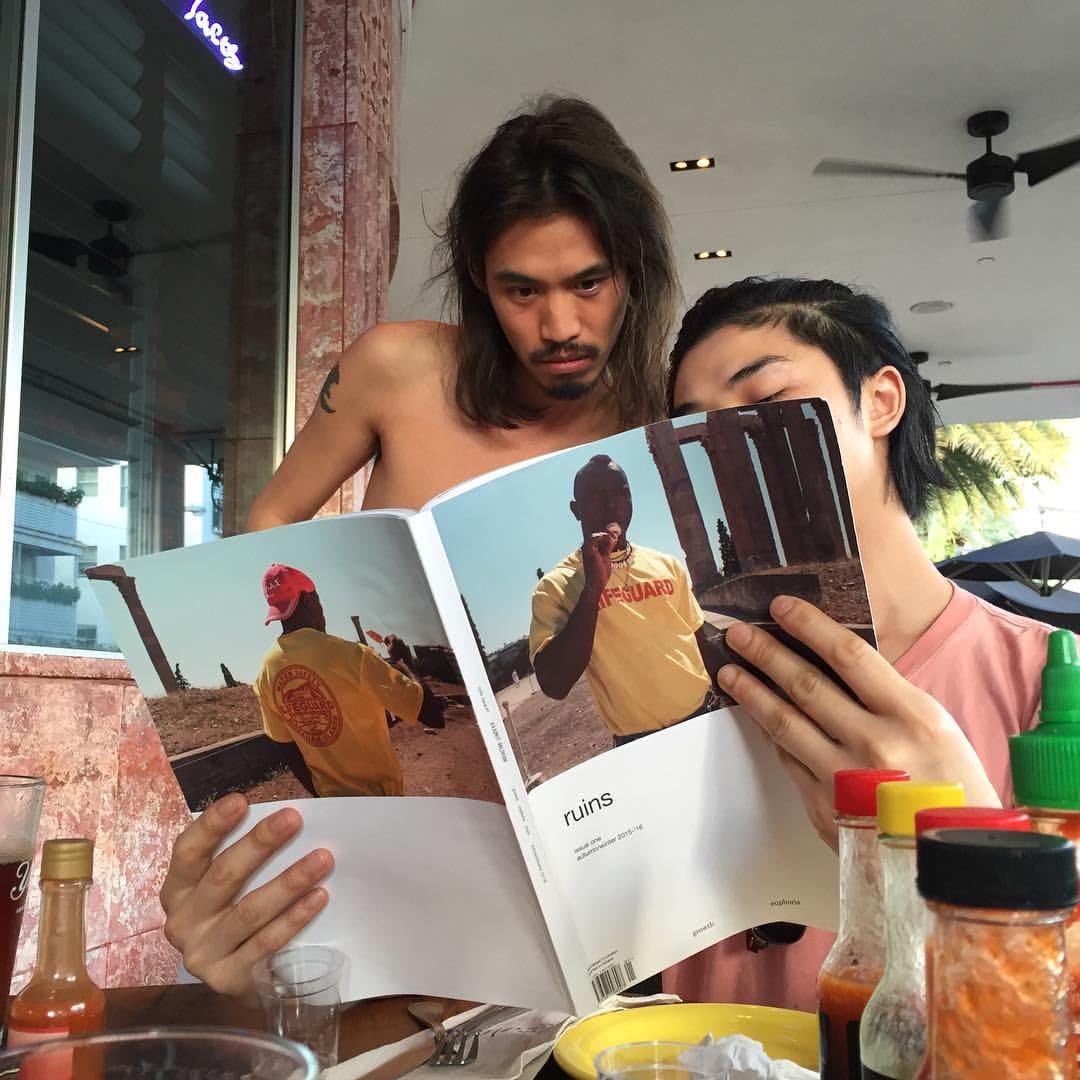

Published in Ruins, vol. 1, 2015, a magazine by Christos Petritzis, which grew out of Greece’s Depression-Era creative scene (and only lasted this one issue!)

When the world ends, everyone will be wearing Old Navy polo shirts and hip hugger jeans. Water will be scarce, food will be at a premium, but there will be more than enough embroidered ball caps, GORE-TEX® zip-ups, American Eagle T-shirts, Von Dutch wristbands, Billabong board shorts, and fake Louis Vuittons. Cotton-poly blends and denim with five percent spandex will be everywhere, fast-fashion stitched together into blankets and tents culled from Ts silkscreened with church camp and car dealership logos and rags emblazoned with A&F and A&E. Patchworks of these excavated signs will be a sign of end times. Or maybe it’s just a fantasy that these brands will become meaningless.

There are already more clothes in the world than we can ever wear. And even the cheapest made ones take almost forever to decompose. There are 7 billion people and together Zara, Forever 21, and H&M alone make about a billion new garments each year. Actually Zara is the only one that manufactures textiles themselves. The rest contract and subcontract the work out to factories in Guangdong and Dhaka.

The average American throws away 68 pounds of clothing each year. The glut is too much for the Goodwills and Salvation Armys that the do-gooders donate them to. The majority are shipped to the developing world, flooding villages with hand-me-downs and knock-offs, and destroying their local garment economies in the process. I remember when I was a kid a story made the local newspaper about a train robber in Africa wearing a Calgary Flames jersey, the specific country was maybe as meaningless to me as the hockey team logo to him. This was the late nineties when the myth of the euphoric Global Village still had some currency.

The end of history, back then, was offered up to invoke the triumph of neoliberal capitalist democracy as an unchallenged ideology and the world’s premiere organizing principle. When the Berlin Wall fell, Francis Fukuyama penned an essay to suggest we were post-Communism and therefore post-history. Fukuyama borrowed from Marx that history has a beginning, middle, and end, he just disagreed with regards to what the inevitable outcome would be. Citing the demise of socialism in the USSR, China’s decollectivization of agriculture, and newly industrialized Asian countries, Fukuyama was certain no grand historical events were on the horizon, and liberalism, capitalism, and democracy were predestined for all—the end. Instead, in the past decades, we’ve witnessed a hollowing out of liberal ideals in Western democracies and a corporate hold over their political systems. And as environmental devastation and exploitation of resources have spread alongside industrialization, the triumph of capitalism over liberalism and democracy is more likely to bring about end times than the end of history.

There’s a myth that the fall of the USSR came about because of blue jeans. It’s true there was a black market for denim and hustlers sold Levis out the back of unmarked vans, but it’s hard to say how much the want for Americana, teen dreams of rock and roll, Hollywood, and denim, really contributed to the regime’s demise. In Belarus, Europe’s last dictatorship, the 2005 uprising disputing phony election results met with a violent police crackdown was chimerically named the Jeans Revolution. Police seized the flags from one of the protest’s leaders, so the story goes, and he resourcefully tied his denim pants around a pole like a flag. It was a loaded symbol since blue jeans evoke the West and freedom, except maybe for the factory workers who make them. In China’s Guangdong province, where it’s estimated 260 million pairs of jeans are produced each year, the sandblasting process is a particular health hazard. Fine-grain sand shot out of high-pressure air guns gives jeans a popular worn-in finish and can lead to a fatal respiratory disease known as silicosis.

The average pair of jeans drinks up 3,479 litres of water in its lifetime, from the irrigation of the cotton to the manufacturing to the numerous washing-machine cycles. Denim with that “used” look can be even more environmentally straining than the average pair of jeans depending how the debris from the sand-blasting process is disposed of. Despite some brands like H&M swearing off sand-blasting, worn-in denim seems to have stayed relatively in-style since the 80s. It may have had its ebbs and flows—in a 2005 editorial called “Faded” New York Times street fashion photographer Bill Cunningham notes the loose worn-in look that had “run its course with the hipsters…is now uniform for young antidesigner guys”—but as the cycle of trends has accelerated (now 52 microseasons instead of just winter, spring, summer, fall) it’s almost as if time has stood still. Worn-in, distressed, and faded denim were big on the runway this year from Gucci to Moschino, and Style.com put words in Jeremy Scott’s mouth suggesting by his “own admission, it needn’t always be novel.”

It needn’t always be because it can’t be anymore, not for longer than a minute anyways. Fashion is as much about the circulation of images as it is about manufacturing, and high-end brands can no longer keep their designs privy to an exclusive audience. In part thanks to sites like Style.com which post complete runway collections online immediately, fast-fashion brands can rip off entire collections in mere weeks. A couple of years ago, Forever 21 had Alexander Wang knock-offs in stores 15 days after the looks were unveiled on the runway. It’s like time sped up so much that it slowed down to a standstill. Look at photos from September 11 and nearly a decade and a half later, what people were wearing on the street then isn’t much different from what people are wearing on the street now. The fashions seem remarkably not dated. History happened but it looks like nothing changed.

In an interview with NPR about fashion in a post-911 world, maternity-wear designer Liz Lange pointed at the trend of luxury-for-less partnerships like Karl Lagerfeld for Macy’s and Donatella Versace for H&M as being the most marked difference before and after. The first of these indeed was Isaac Mizrahi for Target in 2002. Like the era’s neo-liberal policies, in the mid-nineties Mizrahi was conspicuously popular and sold to us as a success story even when he was failing where it counted. Unsuccessful in finding haute commercial success, in 1998 he declared bankruptcy and, four years later, redefined himself with an affordable line for the US’s second-largest discount retailer. Now these sorts of collaborations are common and typically huge commercial successes.

The nineties saw the expansion of neoliberal policies on a global scale. The same porous borders that allowed terrorism into the US, the decade before, encouraged free-trade and the transnational movement of people and goods. It was in the nineties that the textile industry largely left America. The free-market found cheaper workers in China, India, Bangladesh, and Mexico. In 1992, American Levi Strauss workers went on a hunger strike to protest a textile plant moving from San Antonio to Costa Rica. Even though the company had hundreds of millions in annual profits, they were relocating to widen the profit margin even more, replacing the women in Texas sewing for $9.10 with workers who would sew for a few dollars an hour. By 2003, Levi had shut down all of its American plants.

But post-911, the American economy shifted from being obsessed with cheaply manufactured goods to being preoccupied with running a privatized security state. The homeland security industry exploded, and so did demand for information gathering and data analysis services. With wearables there’s some crossover between the information-technology and fashion industries. Wearable tech gadgets that track your heart rate or body temperature add to the glut of privatized data and to the demand for software that will make sense of it and therefore give it value, and these gadgets have the same end-game as most info-tech products—they track people. As computing technology gets small enough to be woven into fabrics, smart textiles will potentially make privacy even more of a luxury. But fashion is about networks of information-technology in a much less futuristic way.

The success of retailers is in part based on the speed at which they can process information from the runway to the factory floor, from the fashion magazine to the retail store. Customer data is Zara’s competitive advantage. Everything in their stores is a runway knock-off, but that’s the same for much of their competitors’ merchandise too. What makes Zara unique is the accelerated speed at which their supply chain can communicate and respond to minute changes in consumer demand. They can get a product from concept to store in 15 days, and managers at their 2,000-plus international stores are responsible for communicating shoppers’ feedback. Their entire supply chain is flexible to it. Inventory is made in small batches with new orders made twice a week. Zara does all the manufacturing itself and has little to no budget for traditional advertising. Its parent company Inditex had profits of over €2.381 billion in 2013.

Inditex’s founding chairman Amancio Ortega Gaona is the second richest person in the world. He famously resists his image being public. Until 1999, no photographs of Ortega had ever been published. Vogue editor Anna Wintour also famously still uses a flip phone. Both Ortega’s and Wintour’s power comes in part from how they control the flow of information and images across communication networks. For both of them, understanding the value of that information translates to being much more protective of their own.

Teenagers around the world lusted after Nike in the nineties the way that Soviet teenagers lusted after blue jeans in the eighties. Logos, a Nike swoosh or Louis Vuitton’s classic monogrammed and Damier print, are easy to knock-off. As companies outsourced their manufacturing to China, a counterfeit industry in the country flourished. But for knock-off manufacturers, access to communications networks would prove a greater hurdle than cheaply producing imitation goods. Counterfeits flooded the market, but in 2008, Louis Vuitton’s parent company LVMH sued eBay and Google in French court for allowing fakes to be sold and listed, respectively, on their sites. The court ordered Google to stop displaying listings for counterfeit rivals when they typed Louis Vuitton or another trademark into the search engine. It turned out, LVMH didn’t have much competitive edge in producing bags at an appealing price and quality, they only had an advantage in controlling the networks of information that communicated how to buy them.

In spite of this big win for luxury brands, counterfeiting still seems to have diluted the value of logos. The fact that downtown cool kids took to wearing them ironically suggested there wasn’t any currency left in the anti-corporate no-logo movement of the nineties because there wasn’t much value left in logos for the corporations behind them in the first place. Today, brands need a much more sophisticated communications strategy than marketing a logo to stay relevant, profitable, and powerful. In the wake of logo fatigue, they’ve set an accelerated pace of production and consumption, which takes an extremely astute communications network to maintain. It’s not enough just to make clothes cheaply, it’s about re-producing your brand through disposable merchandise at a faster rate than nearly any other retailer could possibly keep up with. As a consequence we have more clothes being made than we could ever know what do with and a scale of production that puts increasing strain on the environment. But when the end of history translates into end times, we’ll at least always have something to wear.

Pictured above: Zaina Miuccia, Christos Petritzis, and Preston Chaunsumlit reading Ruins.