The Brutalist was a letdown on many levels, one being I was not expecting the heavy Zionist overtones. Fictional but historically-grounded, the film traces one man’s arc across several watershed moments of the 20th century (not unlike Forrest Gump) — from the Bauhaus to the Holocaust to the inaugural Venice Architecture Biennale. Basically, its purpose seems to be to explain to someone who has a Pinterest-understanding of Brutalism the socio-historical moment that birthed this radical shift in design.

I was assigned a similar project this summer. A magazine had an idea of what images they wanted to run and tasked me with writing an essay that could accompany them — a story of how these monolithic mid-century buildings came to be. In broad strokes, I came to a similar conclusion as the film does, Brutalism was a response to the spiritual devastation of World War II. But the specifics of The Brutalist align the cultural cachet of this design sea change not so subtly with Zionist sympathies. It’s like, for the past ten years, there’s been this fervent reappraisal of Brutalism, and now that raw concrete is on everyone’s moodboards, here comes this big Hollywood epic that co-opts its historical significance premiering at the precise moment when Zionist ideology is fueling a murderous campaign against the people of Gaza.

In the film, the architect’s harshly austere design aesthetic was birthed from the ruthless brutality of systematic ethnic cleansing and his personal experience of imprisonment in a concentration camp. This fictional architect’s buildings and biography have parallels with Marcel Breuer and Louis Kahn, and though both these architects were Jewish and European-born, neither had the same harrowing experience the film’s protagonist does. Hungarian-born Breuer escaped Germany in 1935 and Kahn who was born in modern-day Estonia emigrated to Pennsylvania as a child in 1906. Still they were deeply connected to the existential reckoning borne by the Holocaust. This was the climate they were making work in. What The Brutalist leaves out is that the architectural style of its central figure belongs to a lineage of Modernism driven forward by two men who were sympathetic to Nazi fascism, Philip Johnson and Le Corbusier. That there just isn’t time to engage any of this fraught history is no excuse when a film is three and a half hours long.

Three and a half hours long, and no room either for any complicated feelings around Israel. When the characters discuss moving there, it’s just “time to go home,” no conflict or questioning — even though debates were happening. The Jewish Labor Bund, for example, opposed Jewish settlement in Palestine. Today endorsing a simplified narrative, especially when we’ve witnessed a lifting of the veil on the Nakba’s ongoing consequences, comes across suspect. And the filmmakers made specific choices, like to zhuzh the timeline, juxtaposing the design innovation of tubular steel furniture with a radio broadcast of the UN recognizing Israel. A link is made between the creative trailblazer and the literal pioneer, suggesting a shared historical moment when, in reality, these events occurred 25 years apart.

Shifting gears a bit, here’s the essay I wrote for the second issue of Beyond Noise, examining the concrete architecture of Brazil. Though often retroactively labeled Brutalist, this style emerged from the mid-century São Paulo-based architects called the Paulista school. It was British architects Alison and Peter Smithson who popularized the term “New Brutalism.” Thank you to Morgan Becker for tapping me for the assignment. I played into this zeitgeist-y idea of the dream home, shaped as much by moodboarding mid-century buildings as by digitally-rendered fantasy spaces. I do wonder what happens now, if the mainstreaming of Brutalism in an A24 film will mark the end of this aesthetic fixation and shift the zeitgeist elsewhere. But maybe mainstreaming is an overstatement. When I saw the film last night, there were all of three other people in the theater.

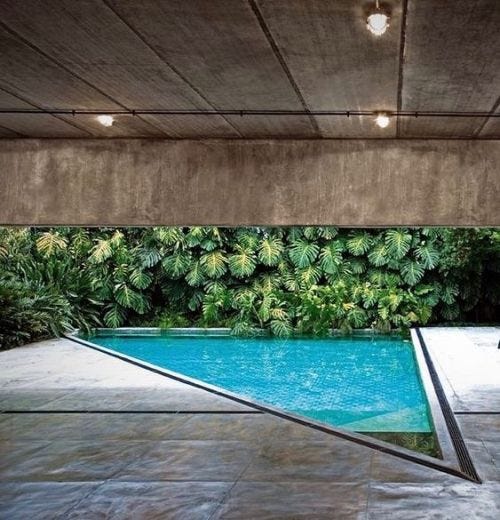

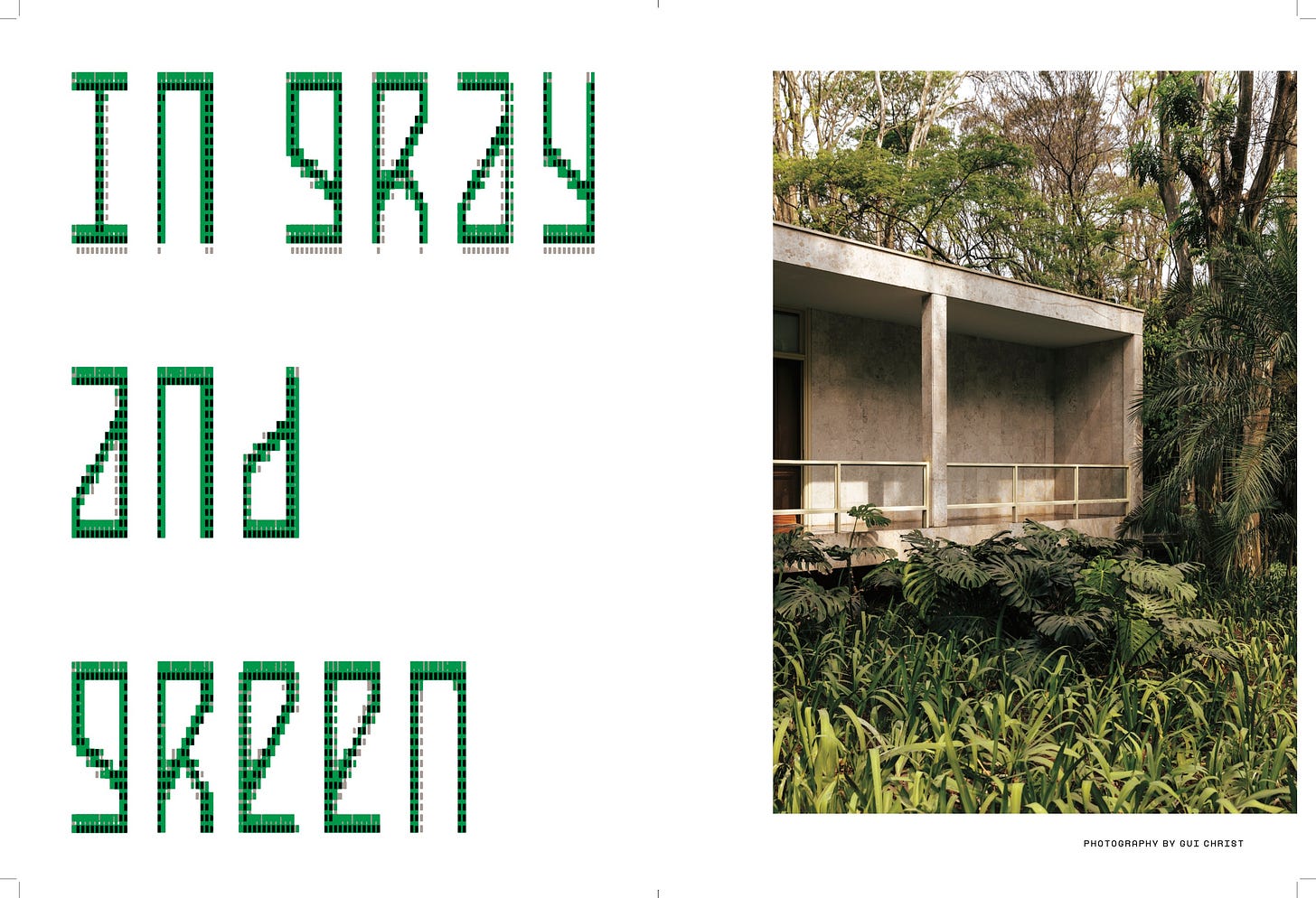

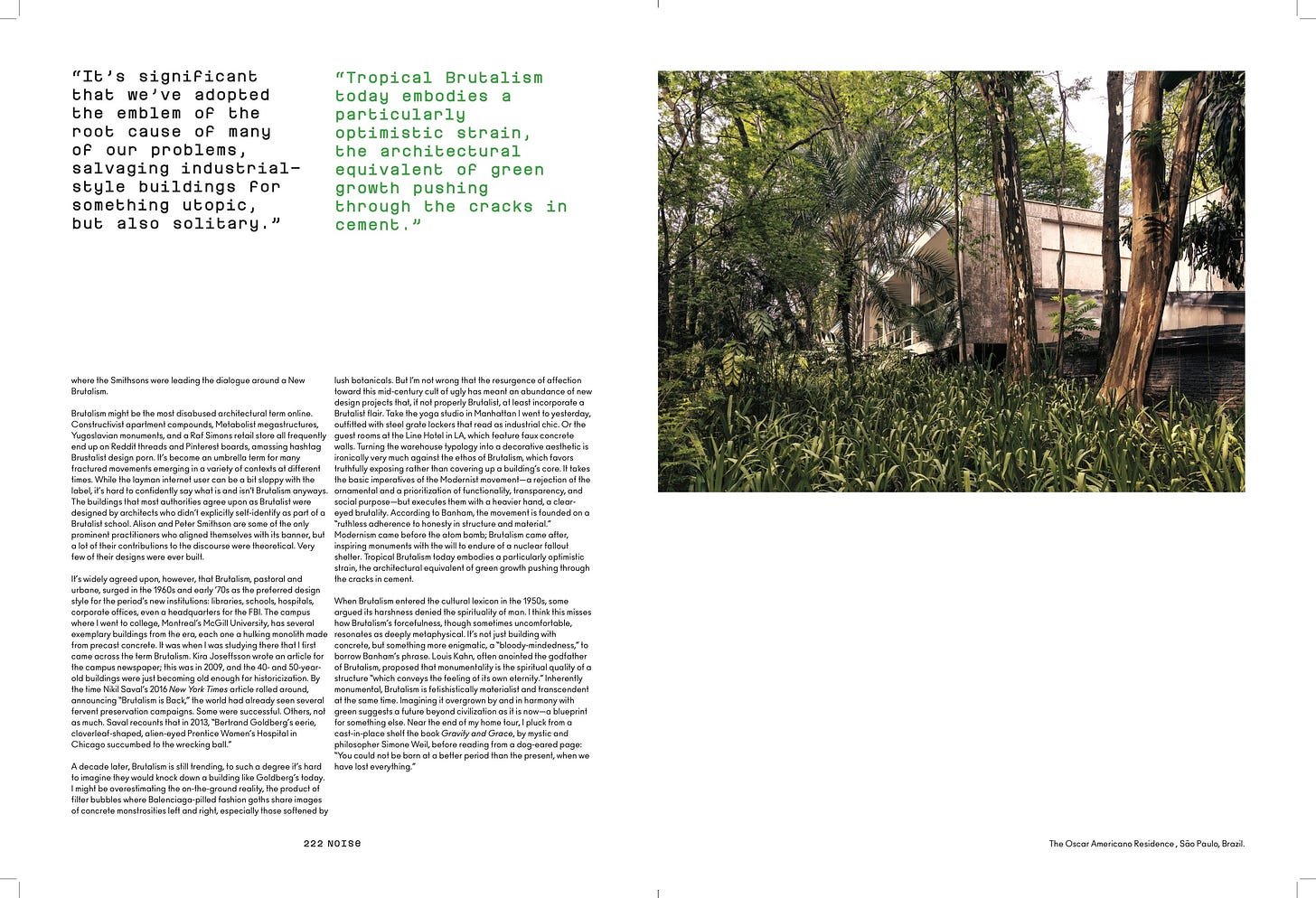

“Welcome to my dream home.” My voice reverberates like it would in a cave as I give you the tour. The concrete is cold to the touch. The walls are fortress-like, unyielding to any crises or the ravages of time. As we walk into the living room, the focal point of which is an indoor garden, I point out that there is a porousness — a tension between solidity and openness that shapes a dynamic interplay between the built environment and natural world. Windows frame verdant vistas of green. Everywhere raw industrial materials and rigid lines are in dialogue with the untamed exuberance of lush foliage. It’s a perfect backdrop for my get-ready-with-me videos where I try on Jil Sander, The Row, and archival Commes des Garçons, my morning-routine videos where I make Moringa-powder lattes before my 7 a.m. cold plunge.

My home is an image — a requirement of “New Brutalism” according to the movement’s pivotal figures, British architects Alison and Peter Smithson, who coined the term to describe their own designs in 1953. A debate emerged with critic Reyner Bahham, who challenged some of the assumptions the Smithsons made. About this concept of image he writes, “Basically it requires that the building should be an immediately apprehensible visual entity.” If that seems obtuse, it’s intentional. Earlier in the same essay, he contends, “Image seems to be a word that describes anything or nothing.” Trying to pin down whether conceptual architecture and image-making architecture existed before Modernism, is a doomed endeavor. Architecture, after the front-facing camera, without a doubt must respond to accelerated visual demands. My dream home is iconic (if that word means anything anymore); it’s also a haptic experience somewhere between a marble palace and a mossy subterranean hideaway. There is gravity — a sense of the weight of material that pixels just don’t translate — and also grace.

I like to think I’m not like other girls but my dream home is a fantasy that’s in vogue, a rugged post-industrial vision of gray and green. Fueled by an ambience of escalating crisis, climate change, and war, our generational hive mind hovers around vintage images and 3D-generated renders, brutal yet pastoral, reimagining hard edges with a soft landing somewhere that looks like Brazil. It’s escapist and also post-apocalyptic. This is after industrialism — a return to nature but not a return to the log cabin, yurt, or other pre-industrial typologies. It’s significant that we’ve adopted the emblem of the root cause of many of our problems, salvaging industrial-style buildings for something utopic, but also solitary. It’s a glam-Thoreau survivalist fantasy hinging on retreat from society — a luxury bunker from which to broadcast impeccable taste and aspirational wellness. The austerity offers a minimalism that quiets the noise but doesn’t lie about the outside world’s brutality. It’s here in this stronghold of elegant restraint that I would finally meditate.

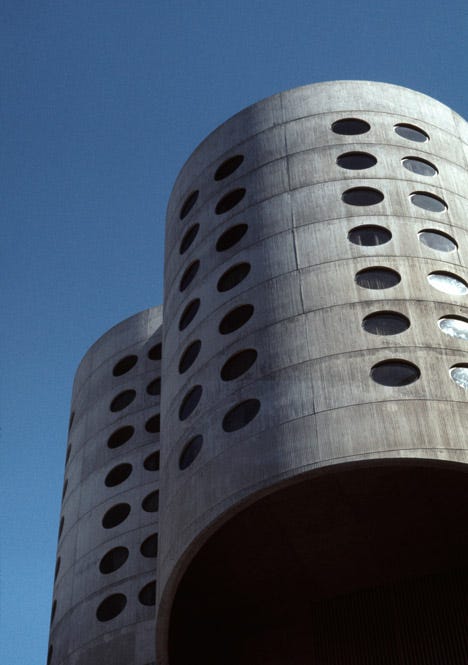

Concrete architecture dates back to Mesopotamia, I tell you as the tour leads into my sparsely furnished bedroom. I make myself comfortable lounging on the low-slung bed draped in a tangle of 100 percent French flax linen sheets before unpacking this history. It was the Romans who elevated the lime-based mortars that had been used for thousands of years by adding volcanic ash, which allowed for the construction of monumental structures like the Colosseum and the Pantheon, both still standing today. But it wasn’t until the late 19th century that reinforced concrete came along. This ingenious melding of steel and concrete distributed more evenly the stresses of complex loads. New and improved, no longer as vulnerable to cracks, concrete became the go-to material for the Industrial Revolution. With its added merits of versatility (it can be molded into many shapes and sizes) and durability (it isn’t prone to decay or fire like wood), concrete became the standard for storage and manufacturing facilities, of which there was a growing need.

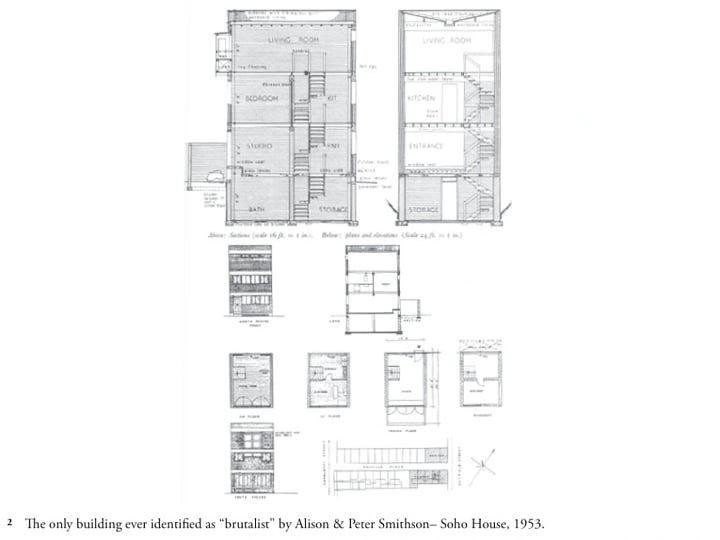

By the time the Smithsons imagined applying the concrete warehouse typology to a residential home, it was already a pervasive, recognizable element of the industrialized urban landscape. In 1953, the husband and wife pair designed (but never built) a home for a bombed-out site in London that’d been devastated during WWII. They told Architectural Digest, “It is our intention in this building to have the structure exposed entirely, without internal finishes wherever practicable. The Constructor should aim at a high standard of basic construction as in a small warehouse.” Appropriating the common materials and forms of the industrial landscape, they called their aesthetics “as found.” Betraying the bleakness of the postwar psyche, they described their design as “a house for a society that has nothing.”

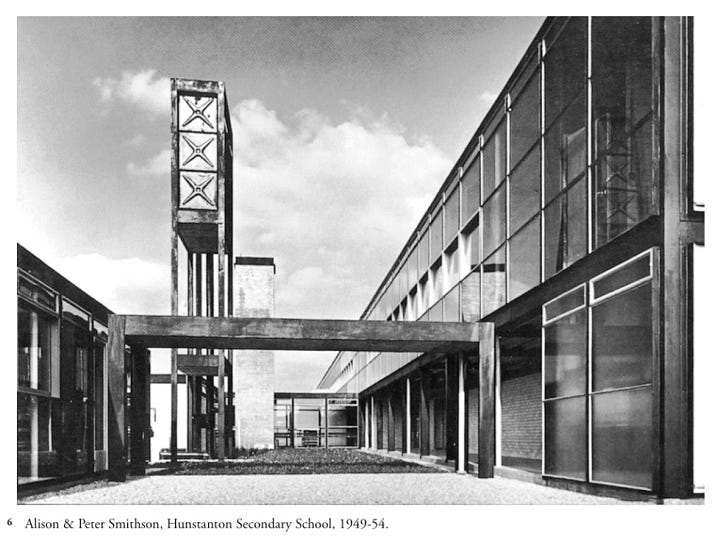

While it may have grown out of ruin and a sense of lack, there’s an optimism in the Smithsons’ gesture of adaptation. And while the home was never approved to be built (there are still today regulations in London neighborhoods forcing strict consistency of historic building styles), the project stirred up a controversy that propelled the term “New Brutalism” into the air. A year later, the architects completed Hunstanton, a secondary school in Norfolk designed for 480 students. Raw unfinished steel and concrete feature heavily, as do large windows and an H-shaped floor plan conceptualized around adaptable and flexible rooms, their usage open to various and changing needs of pedagogy. Hunstanton is agreed upon as the earliest textbook example of Brutalism ever built.

Although the Brutalist school of architecture has British roots, and its first backdrop, Norfolk’s semi-urban flat terrain, would be described as anything but lush, today’s collective imagination has glommed onto another iteration. At the moment, there’s a pining for austere concrete structures merging with dense leafy growth evident in both new buildings, renovation projects like the Oakland Museum, and image boards seemingly everywhere. What we understand as Brutalism today is sometimes a label retroactively applied to movements which emerged in parallel to the discourse the Smithsons provoked in mid-century England. Brazil is home to what’s been labeled Tropical Brutalism. But in the 1950s, when it emerged, 6,000 miles away from the New Brutalism exemplified by Hunstanton, it was called the Paulista school. This avant-garde headquartered in São Paulo is defined by its practitioners’ use of raw concrete, clean lines, and functionalist yet expressive forms. Located on a plateau in the highlands bordering the tropical rainforest, the landscape of Brazil’s most populous city is famously fertile and green.

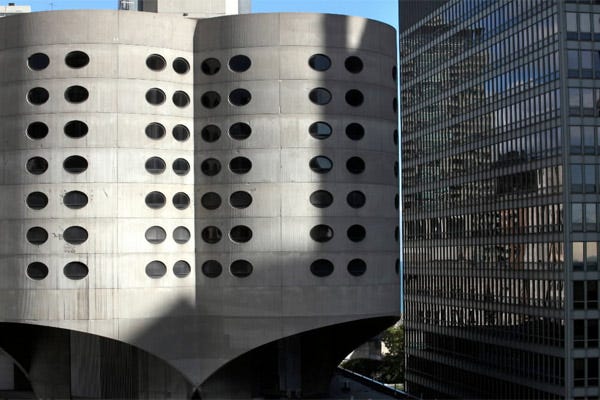

There was cultural exchange happening between Europe and Brazil in those years. Lina Bo Bardi, whose name is synonymous with Brazilian Modernism, was born and educated in Italy, but after the Second World War, life became difficult because she and her husband had participated in the resistance movement. Together they found a new home in Brazil. Immersed in the culture there, the Italian rationalism of Bo Bardi’s architectural training adopted a new expressiveness. She designed projects which would both influence and converse with the then-emerging Paulista school. The Paulista architects were all Brazilian-born. The work of Paulo Mendes da Rocha, one of the central figures of the Paulista movement, feels closely aligned to today’s Tropical Brutalist moodboards. But a lot of the work of his fellow Paulista School architects, like João Batista Vilanova Artigas, Joaquim Guedes, and Decio Tozzi, also corresponds perfectly with what we classify as Brutalism retroactively, even though they never adopted this banner themselves. Maybe there would’ve been more shared language between this wave of concrete architecture and what was being built in other places in the world, but the political situation changed in Brazil in 1964. A U.S.-backed coup saw a right-wing military dictatorship take power and the country closed off. In this climate, there were also fewer opportunities for card-carrying communists like da Rocha and Artigas. Their political affiliations shouldn’t be a surprise: Modernism more broadly and Brutalism specifically emerged as style of building inspired by socially egalitarian ideals.

If Brazil had been less isolated in the 1960s and 70s, would their architecture have been influenced more in the global conversation around Brutalism? It’s hard to speculate. Partly because it’s logical that the oppressive political environment also influenced the style of heavy, imposing, and immovable forms that proliferated during those years. You could argue something similar in the Soviet context. Both regimes, characterized by their oppressive nature and obsession with modernization, embarked on grand building projects that became monumental symbols of power, vividly reflecting the era’s stylistic preoccupations. And yet, this is not the only context from which Brutalism emerged. There are many examples from the 1950s, 60s, and 70s all over the world — including in the U.S., Britain, Canada, France, Australia, and Japan. And there are many points of contact between what we understand as Brutalism and what’s been designated Tropical Modernism — climate-responsive architecture in a post-colonial context across South and Southeast Asia and Africa. Many of the architects building in their home countries in this period had been trained in Britain, where the Smithsons were leading the dialogue around a New Brutalism.

Brutalism might be the most disabused architectural term online. Constructivist apartment compounds, Metabolist megastructures, Yugoslavian monuments, and Raf Simons retail store design all frequently end up on Reddit threads and Pinterest boards accumulating hashtag Brutalist design porn. It’s become an umbrella term for many fractured movements emerging in a variety of contexts at different times. While the layman internet user can be a bit sloppy with the label, it’s hard to confidently say what is and isn’t Brutalism anyways. The buildings that most authorities agree upon as Brutalist are built by architects who didn’t explicitly self-identify as part of a Brutalist school. Alison and Peter Smithson are some of the only prominent practitioners who aligned themselves with its banner, but a lot of their contributions to the discourse were theoretical. Very few of their designs were ever built.

It’s widely agreed upon, however, that Brutalism, pastoral and urbane, surged in the 1960s and early 70s as the preferred design style for the period’s new institutions: libraries, schools, hospitals, corporate offices, even a headquarters for the FBI. The campus where I went to college, Montreal’s McGill University, has several exemplary buildings from the era, each one a hulking monolith made from precast concrete. It was when I was studying there that I first came across the term Brutalism, Kira Joseffsson wrote an article for the campus newspaper. This was 2009 and the 40- and 50-year-old buildings were just becoming old enough for historicization. By the time Nikki Saval’s New York Times article rolled around in 2016 announcing “Brutalism is Back,” the world had already seen several fervent preservation campaigns. Some were successful. Others not as much. Saval recounts that in 2013 “Bertrand Goldberg’s eerie, cloverleaf-shaped, alien-eyed Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago succumbed to the wrecking ball.”

A decade later, Brutalism is still trending, and to such a degree it’s hard to imagine they would knock down a building like Goldberg’s today. I might be over-estimating the on-the-ground reality, the product of filter bubbles where Balenciaga-pilled fashion goths share images of concrete monstrosities left and right, especially those softened by lush botanicals. But I’m not wrong that the resurgence of affection toward this midcentury cult of ugly has meant an abundance of new design projects that, if not properly Brutalist, at least incorporate a Brutalist flair. Take the yoga studio in Manhattan I went to yesterday outfitted with steel grate lockers that read as industrial chic. Or the guest rooms at the Line Hotel in L.A. which feature faux concrete decals on the walls. Turning the warehouse typology into a decorative aesthetic is ironically very much against the ethos of Brutalism, which favors truthfully exposing rather than covering up a building’s core. It takes the basic imperatives of the Modernist movement, a rejection of the ornamental and a prioritization of functionality, transparency, and social purpose, but executes them with a heavier hand, a clear-eyed brutality. According to Banham, the movement is founded on a “ruthless adherence to honesty in structure and material.” Modernism came before the Atom bomb; Brutalism came after, inspiring monuments with the will to endure of a nuclear fallout shelter. Tropical Brutalism today embodies a particularly optimistic strain, the architectural equivalent of green growth pushing through the cracks in cement.

When Brutalism entered the cultural lexicon in the 1950s, some argued its harshness denied the spirituality of man. I think this misses how Brutalism’s forcefulness, though sometimes uncomfortable, resonates as deeply metaphysical. It’s not just building with concrete but something more enigmatic, a “bloody-mindedness,” to borrow Banham’s phrase. A decade before, Louis Kahn, often anointed the godfather of Brutalism, proposed that monumentality is the spiritual quality of a structure “which conveys the feeling of its own eternity.” Inherently monumental, Brutalism is both fetishistically materialist and transcendent at the same time. Imagining it overgrown by and in harmony with green suggests a future beyond civilization as it is now — a blueprint for something else. Near the end of my home tour, I pluck from a cast-in-place shelf the book Gravity and Grace, by mystic and philosopher Simone Weil, before reading from a dog-eared page: “You could not be born at a better period than the present, when we have lost everything.”

This is important, recognizing how an ideology gets embedded in a historical narrative film. And in a simplistic sense: this happens and because of that this happens. The arguments about Zionism among Jewish intellectuals was fraught, understandably so. Minds such as Einstein's and Benjamin's and Kafka's were very ambivalent, and because doubt and trouble about the establishment of a Jewish state is removed from Zionism's history, it has allowed Americans not to see its drastic problems, not see people taken forcibly off their land. Not see the Israeli government as it is, as it behaves. Its brutality. Which brings me back to The Brutalist. I'll see it because of your essay.

The author appears to have issue with jewish folks having a homeland in the middle east after being forced out of Europe and mostly exterminated.

The movie brings up important questions like how many other architects, scientists, musicians or artists that would have progressed humankind were lost in the Holocaust?

Whitney completely ignores and turns a blind eye to the launched offensive of murder, rape and hostage taking of Oct 7 that was meant to replicate a second holocaust. The author goes so far as to try and discredit the jewish contributions to Brutalist architecture by handing credit to those that came before. Everyone knows that before anything came something else, and so on. What a loaded piece of trash.