You can tell Tony Cox thinks it’s hilarious when he says he’s become an art dealer. He flashes his teeth and giggles, a series of jolly hyperventilations, like his impersonation of this mythically sleazeball figure is some cosmic joke. Even if it might seem unexpected, or simply a part of Cox’s self-effacing jester routine, the self-taught artist and former pro skater is serious about the new guise, driven to protect the sacredness of art that the industry juggernauts don’t seem to prioritize. And it turns out he’s got a knack for getting works into good homes, having found his own idiosyncratic way of doing it, out of his Manhattan apartment, the exact location of which is a secret. Club Rhubarb is what Cox has anointed the project.

An ancient elevator takes you up to the club’s headquarters, a modest loft in a mixed-use building, which once housed offices for Bernadette Corporation and later Telfar. Cox plans Club Rhubarb openings and visits in the daytime, “doing it here it’s all about the ambient light,” he says, preferring the late afternoon glow that pours in through the big south-facing windows to illuminate the artworks. The floors are painted kelly green, slightly chipped and showing through in spots with the neon yellow they were colored when he first moved in, over a decade ago. Adding to the vibe are big leafy plants and burning incense. Except for the bathroom, everything from the kitchen sink to Cox’s sleeping quarters are in this one room where the art is also installed. A staircase of simple wooden construction painted white leads to a lofted bed. Sometimes Cox brings down from this treehouse-nook a small mattress and leather pillows which he sets up on the floor, an invitation to lounge like a cat in the sunshine while he smokes out the window. “It’s a personal experience,” he says. “I want people to sit down and take in the art, see it in the light, the way the colors shift, as opposed to some ground-floor space where someone swirls around but doesn’t actually look at the show.”

Cox didn’t go to art school. The Louisville native made a name for himself skateboarding in California in the nineties — he’s 47 now. But while he was getting sponsors (over the years: Liberty, ATM Click, Duffs, Union Wheels, Independent, Silver Star, Half Life, Supernaut, iPath, Satori, Young Coconuts, and Uprise) he was also making art. A friend at a skate magazine lent him a camera and would develop his film for free. He’d sew on the postcards he’d mail to friends. He was hanging out places where this stuff cross-pollinated, like Aaron Rose’s gallery Alleged, the tail end of Cox’s skate career intersecting with the beginning of his art career. By the time he was the cover star of Transworld Magazine (like skating’s Vogue) in 2004 — it’s an insane photo where he’s at least ten feet above the pavement doing what’s called a Japan Air — he’d already shown at Deitch Projects. Along with KAWS and Dash Snow, he was one of the artists with skate or graffiti ties in the Session The Bowl group exhibition (2002–03), their works mounted in a skateboard bowl built inside the gallery. The blatant attempt at co-opting subculture wasn’t without friction. “I tried to bring my friends to see my piece and Jeffrey Dietch was like ‘you can’t go up there,’” recalls Cox. “Two seconds later someone shoves him and his glasses go flying, and then A-Ron [Bondaroff] grabs the mic saying, ‘Corporate America can’t buy us.’” For Cox, who later showed at other blue-chip operations like Salon 94 and Marlborough, it was the first of many weird experiences over multiple decades that led him to want something different with Club Rhubarb.

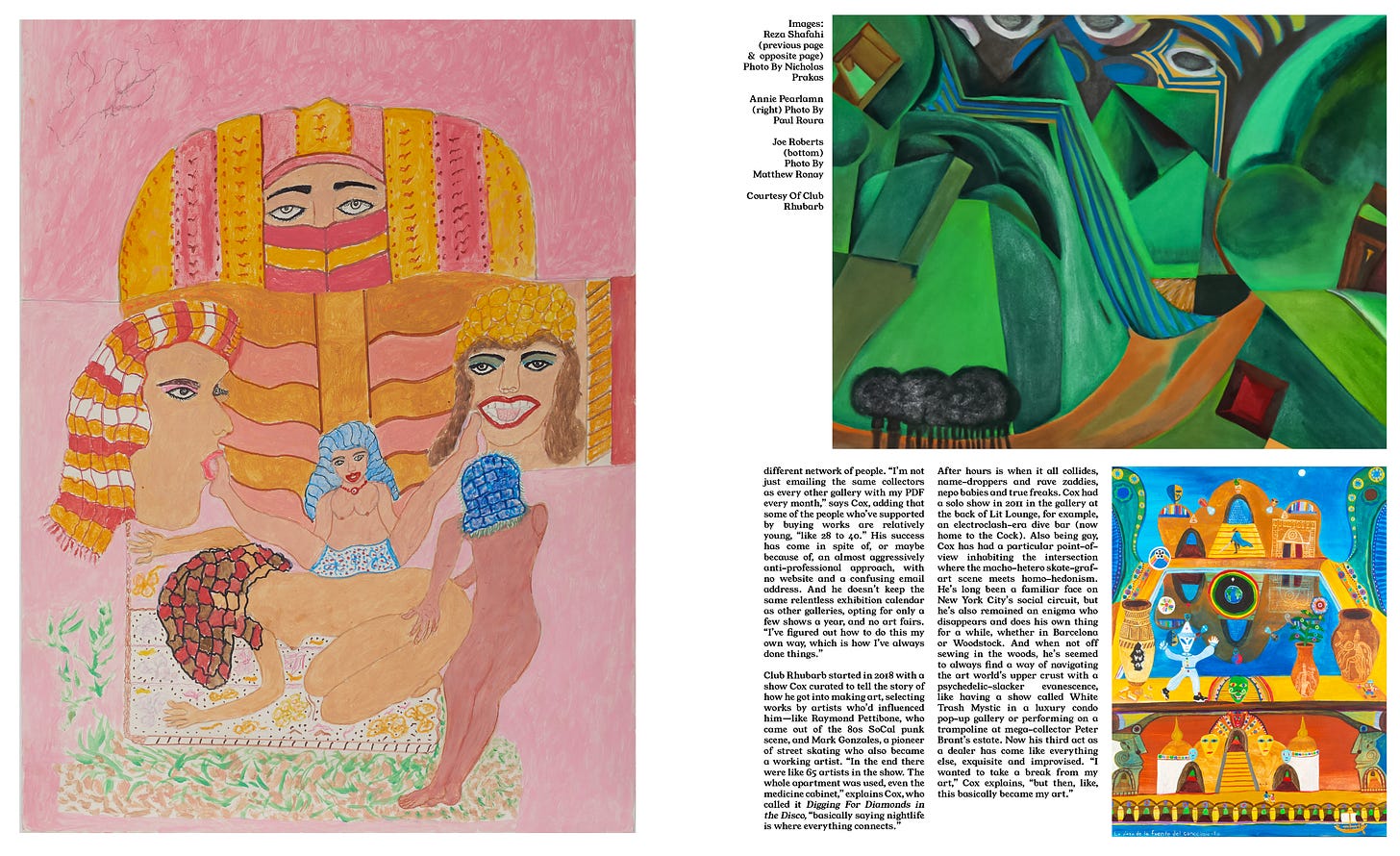

Cox hates the term “outsider artist” but it’s a lazy way to say many of the people he’s worked with have taken unconventional paths to get where they are. Exhibitions at Club Rhubarb have included Sal Salandra’s needlepoints of homo BDSM scenes, the septuagenarian’s debut solo show which earned an Artforum critic’s pick; drawings by Reza Shafahi, a retired pro wrestler from Iran whose collaborations with his artist-son Mamali launched a drawing practice that has since replaced Shafahi Senior’s gambling addiction; and an exhibition by Joe Roberts, AKA LSDworldpeace, featuring paintings inspired by the artist’s DMT trips plus a paper maché diorama referencing ingredients for at-home mescaline synthesis. “More interesting than where someone went to school or what exhibitions they’ve been in I think is the narrative of someone’s life where the work came from,” says Cox, who commissions gay publishing impresario Michael Bullock to tell these stories in the press releases. (Bullock is also responsible for first introducing Cox to the Shafahis, as well as to me.) “I’d call them all unsung heroes,” says Cox of his artists. “And whether you like love or hate their art, you can’t deny some of their stories.”

Most recently at Club Rhubarb was Annie Pearlman’s Connect To Network (2022), colorful paintings of bold squiggly shapes suggesting urban grids and rural roads. A meditation on environment, the series evolved from contrasting New York City, where the artist lives, and Vermont, where she grew up and returned temporarily during the pandemic. While Pearlman is maybe the opposite of an outsider artist, her boyfriend and parents are all artists and she grew up in the orbit of the Vermont Studio Center, she fits right into Cox’s schedule because her work and person are shot through with a verve that’s raw and unpretentious — maybe it’s one of those things where opposites become the same. In November, I organized a reading for her show’s finale, the apartment packed with friends and strangers huddled cross-legged, surrounded by the oranges and greens of her paintings, the magic of the space actualized with many butts sharing the yarn rug that covers much of the painted-cement floor.

Cox didn’t start Club Rhubarb with big intentions to be an art dealer, but one of the reasons it’s worked is because his years haphazardly straddling different realms means he knows a different network of people. “I’m not just emailing the same collectors as every other gallery with my PDF every month,” says Cox, adding some of the people who’ve supported by buying works are relatively young, “like 28 to 40.” His success has come in spite of, or maybe because of, an almost aggressively anti-professional approach, with no website and a confusing email address. And he doesn’t keep the same relentless exhibition calendar as other galleries, opting for only a few a year, and no art fairs. “I’ve figured out how to do this my own way, which is how I’ve always done things.”

Club Rhubarb started in 2018 with a show Cox curated to tell the story of how he got into making art, selecting works by artists who’d influenced him — like Raymond Pettibone, who came out of the 80s So-Cal punk scene, and Mark Gonzales, a pioneer of street skating who also became a working artist. “In the end there were like 65 artists in the show. The whole apartment was used, even the medicine cabinet,” explains Cox who called it Digging For Diamonds in the Disco, “basically saying nightlife is where everything connects.”

After hours is when it all collides, name-droppers and rave zaddies, nepo babies and true freaks. Cox had a solo show in 2011 in the gallery in the back of Lit Lounge, for example, an electroclash-era dive bar (now home to the Cock). Also being gay, Cox has had a particular point of view inhabiting the intersection where the macho-hetero skate-graf-art scene meets homo-hedonism. He’s long been a familiar face on New York City’s social circuit, but he’s also remained an enigma who disappears and does his own thing for a while, whether in Barcelona or Woodstock. And when not off sewing in the woods, he’s seemed to always find a way of navigating the art world’s upper crust with a psychedelic-slacker evanescence, like having a show called White Trash Mystic in a luxury condo pop-up gallery or performing on a trampoline at mega-collector Peter Brant’s estate. Now his third act as dealer has come like everything else, exquisite and improvised. “I wanted to take a break from my art,” Cox explains, “but then, like, this basically became my art.”

Order Issue 22 of Editorial Magazine

Cover featuring Sofie Royer shot by Kyle Keese

Contributors: Ottessa Moshfegh, Turnstile, Kyler Garrison, Sofie Royer, Lena Dunham, Alissa Bennett, Harley Weir, Liara Roux, Cormio, Teng Yung Han, Leomi Sadler, Eyedress, Éamonn Freel, Mas Guerrero, Sara Yukiko Mon, Snail Mail, Chris Black, Hilma af Klint, Agnes Pelton, Brie Moreno, Emma Kunz, Micah E. Wood, Ancco, Catherine Mulligan, Alexis Gross, Rebecca Storm, Dr.Phoebe Friesen, Leigh Ledare, Aramis Gutierrez, Olivia Whittick, Kyle Keese, Una Farrar, Jeremy Jude Lee, Max Keene, Gagalalala, Erika Houle, Razy Faouri, Gitte Maria Möller, Chris Lloyd, Claire Milbrath, Theodora Allen, Maja Ruznic, Darby Milbrath, Elise Lafontaine, David Rappeneau, Elisa Voto, Jennifer Carvalho, Tony Cox, Club Rhubarb, Whitney Mallett, Reza Shafahi, Annie Pearlman, Joe Roberts, Haley Mlotek, Felipe Bolivar E-Bugs, Jaxon Whittington, Shannon Cartier Lucy.